By Cranmer

As Cabinet Ministers have been blindsided by developments in the Three Waters legislation, the events of last Wednesday night give a glimpse of the power politics that are at play within government.

As the furore over the government’s attempted entrenchment of the anti-privatisation provision within the Three Waters legislation continues to buffet the government, Ministers could be forgiven for thinking that their ‘no surprises’ policy has been replaced with something rather more dramatic.

Last week, the Prime Minister was blindsided when Barry Soper asked for an explanation about the expansion of elements of the reforms to include geothermal and coastal waters. Ministers Robertson and Woods similarly both confessed to not knowing anything about the change. It gave the impression of a Cabinet that had lost its grip on Three Waters. More broadly, it raised questions as to who is actually in charge.

Over the weekend, Fran O’Sullivan’s opinion piece hinted at some of the answers. The article focused on David Parker’s push back on co-governance in the resource management reforms and revealed that “he came under ‘strong pressure’ to ensure New Zealand’s new planning regime was governed on an equal basis with Māoridom.”

But notably O’Sullivan also suggested that “arguably, Labour is already running a system of ‘co-governance’ within its own Government”:

Nevertheless, it is no easy matter for a minister to speak openly on these issues given the power that Labour’s 15-strong Māori caucus currently exerts within the Government.

And the fact that opposition political parties like National, Act and NZ First, which has re-emerged as a potential political force, have clear concerns about the expansion of co-governance and are all opposed to the Three Waters legislation where Māori have a co-governance role on the regulatory side.

That pressure is compounded as arguably, Labour is already running a system of “co-governance” within its own Government with the 15-strong Māori caucus having chalked up considerable policy victories.

Led by deputy Labour leader Kelvin Davis, it comprises 15 members — what Justice Minister Kiritapu Allan refers to as the “first 15.” Labour’s Māori caucus also holds six of the seven Māori electorate seats and boasts six ministers.

It’s known that Parker had to face down that vigorous Māori caucus — which had lined up with powerful iwi interests — to ensure co-governance was not inserted into the Resource Management Act replacement legislation.

It was a theme developed by Chris Trotter in his article yesterday in which he questioned whether Labour has become a co-governed party.

The outrage expressed over entrenchment has only made those questions grow louder.

Political editor, Jane Patterson, in an RNZ article last night called ‘Power Play’ wrote that “Apparently without the knowledge of the prime minister, or the man who runs the business of the House, Chris Hipkins, a 60 percent entrenchment clause preventing the privatisation of water assets was voted into the legislation – with Labour’s support.” Patterson goes on:

Hipkins was more blunt saying the ‘last he heard’ the proposal was for 75 percent, ‘which would have failed with only Labour and the Greens supporting it’.

I wasn’t aware until after the fact that that had been lowered to 60 percent; I wasn’t in the House at the time that it happened.

Nanaia Mahuta as the responsible minister, however, knew exactly what was going on.

Patterson gets to the heart of the matter. Minister Mahuta did know exactly what was going on and, importantly, was the responsible minister. Whilst Ardern, Hipkins and some of their colleagues claim not to be aware of what occurred in the House, consider what exactly did occur.

Last week the Water Services Entities Bill was going through the ‘Committee of the Whole House’ stage of the process. It is where the House sits as a committee and considers the details of the Bill one final time before the third reading. It is similar to a debate although the speeches are shorter and the MPs are working their way through the Bill and voting on amendments.

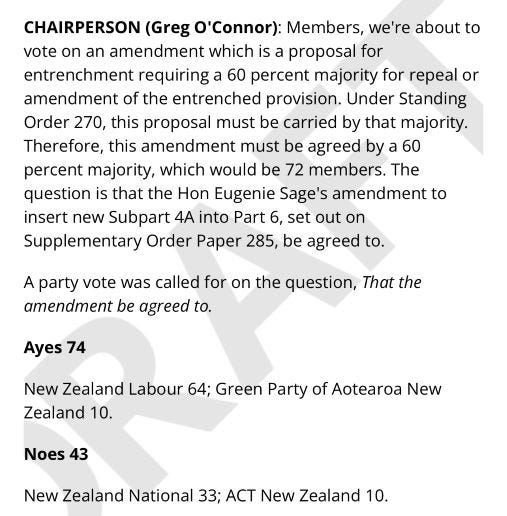

In this case, a party vote was held for each proposal which meant that a party whip or spokesperson needed to vote all of their party’s vote either for or against each proposal. That’s important because it wasn’t just those few members in the debating chamber at the time that were voting – each party was in effect expressing its unanimous position on each of the items considered.

Typically, caucus approval is required for a party position to be expressed in Parliament but when sitting under urgency those rules are modified to take account of the compressed time. When under urgency, a Minister (for the government) and a relevant spokesperson (for each opposition party) who are present in the debating chamber are authorised to apply their party’s votes as they see fit.

Given that Minister Mahuta is the Minister leading these reforms and was present in the debating chamber at the time, it is highly likely that she was authorised to instruct Labour’s whip how to apply their party’s votes. Therefore when the Minister stood up to speak in support of the entrenchment proposal made by the Greens and stated that it would ‘test the will of the House’, it is probable that she did so whilst controlling all of Labour’s votes on the matter.

A short time later, the entrenchment provision was considered and Labour’s Chief Whip, Dr Webb stood up and declared 64 votes in favour. We can assume that Webb acted on the instructions of a duly authorised Labour Minister – probably Mahuta. So whilst Ardern, Hipkins and others were not present in the debating chambers, they had entrusted their votes to one of their colleagues, to be applied as he or she saw fit.

Shockingly however, Mahuta did not even think it was necessary to give her Prime Minister or the Leader of the House, a heads-up that a matter with constitutional implications would be voted on, if only as a courtesy.

By sending the Bill to the Business Committee for further consideration (and thence back to the ‘committee of the whole’), Ardern and Hipkins are effectively disputing the manner in which their votes were applied. They are, in effect, questioning the judgment of one of their Cabinet colleagues on one of their biggest policy reforms. It will be a significant test for Ardern.

Playing devil’s advocate for a moment, Mahuta will argue that Cabinet agreed in April to attempt to entrench this provision albeit at the 75% threshold. So the debate around the Cabinet table about whether to entrench policy items has been completed as far as she is concerned. The Minister tried to reach the 75% level and when it wasn’t possible, adopted the lower level, which by the way, was being floated by at least two of the constitutional law academics who have now flipped and signed an open letter warning of the dangerous precedent that it would set.

In order to keep the pressure on National and Act it wasn’t practical to drop the level until the last minute. Everyone agreed to sit under urgency and therefore knew what that would mean with regards to timing and consultation. Labour authorised the relevant people to apply their votes as they saw fit – which is what happened. Perhaps Mahuta’s biggest challenge is that Labour voted in a manner contrary to Crown Law advice on a constitutional matter, but even then she will claim to have Cabinet backing.

Who knows how this will play out. There is a general expectation that the Bill will be sent back to the ‘committee of the whole’ for the entrenchment provision to be removed but Mahuta and the Māori caucus have been notably quiet on the issue. Maybe the provision will be put into a stand-alone ‘anti-privatisation’ bill which will stand or fall on its own merits. Whatever the outcome, it may give more insight into the extent to which the country is being co-governed.