By Cranmer

According to the government’s own projections the Three Waters debt will only grow over time. We will never escape it and eventually it will tear the country apart.

The financing of Three Waters has been almost entirely overlooked by financial analysts and media commentators despite the fact that the massive debt required to fund the planned shakeup of our water infrastructure could be as risky for the nation’s finances as Muldoon’s Think Big projects of the 1970s-80s.

Research provided to the government has calculated that between $120bn to $185bn in investment is needed to maintain and improve New Zealand’s water infrastructure. What has been left mostly unsaid is exactly how much of this will be funded by debt and how will it be repaid.

The information we do have, however, is hardly reassuring. Government documents show the debt will keep growing and there are no plans for it to be repaid in the foreseeable future. It is effectively perpetual debt on a massive scale.

What makes it even more alarming is that this will be an interest-only financing, in part because there is not enough free cashflow in the system to allow for repayment of capital. It’s just like getting a credit card and immediately maxing it out. Next year when you get a pay rise and your credit limit increases you immediately max the credit card out again. You only ever pay the interest on the card and you have no plan to ever pay it off.

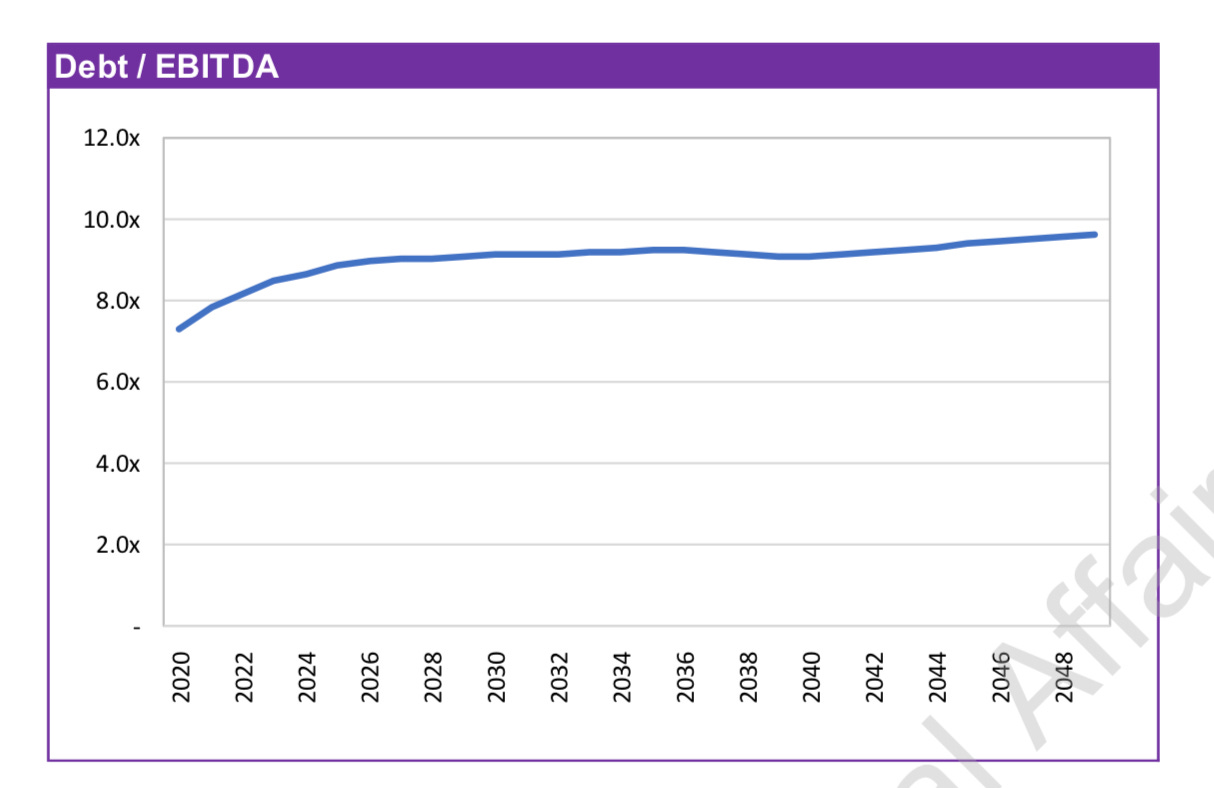

Look at the chart below taken from page 54 of the government’s Information Memorandum on the Three Waters’ debt. For the purposes of this forecast it assumes that the financing starts in 2020 although the actual intended start date is 2024. The chart expresses indebtedness as the ratio of debt to EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation). This ratio is commonly referred to as the leverage ratio. The chart shows that leverage will begin at just below 8:1 (or 8x) at the start of the financing before quickly rising and settling at the long term average of 9x which the government has calculated over a 30-year model. By 2048 leverage is creeping closer to an eye-watering 10x. At these high levels of leverage the financing is exceedingly risky.

Leverage of 9x means that if the water services entities have EBITDA of $1,000 they will borrow $9,000. If earnings (EBITDA) of the water services entities increase by 7% to $1,070 then that will increase the available amount that the water services entities can borrow by an additional $630. In simple terms, the increased earnings increases the credit limit on their credit card, and the water services entities will immediately borrow that extra money from their lenders thereby increasing total debt to $9,630. This is forecast to occur year-on-year.

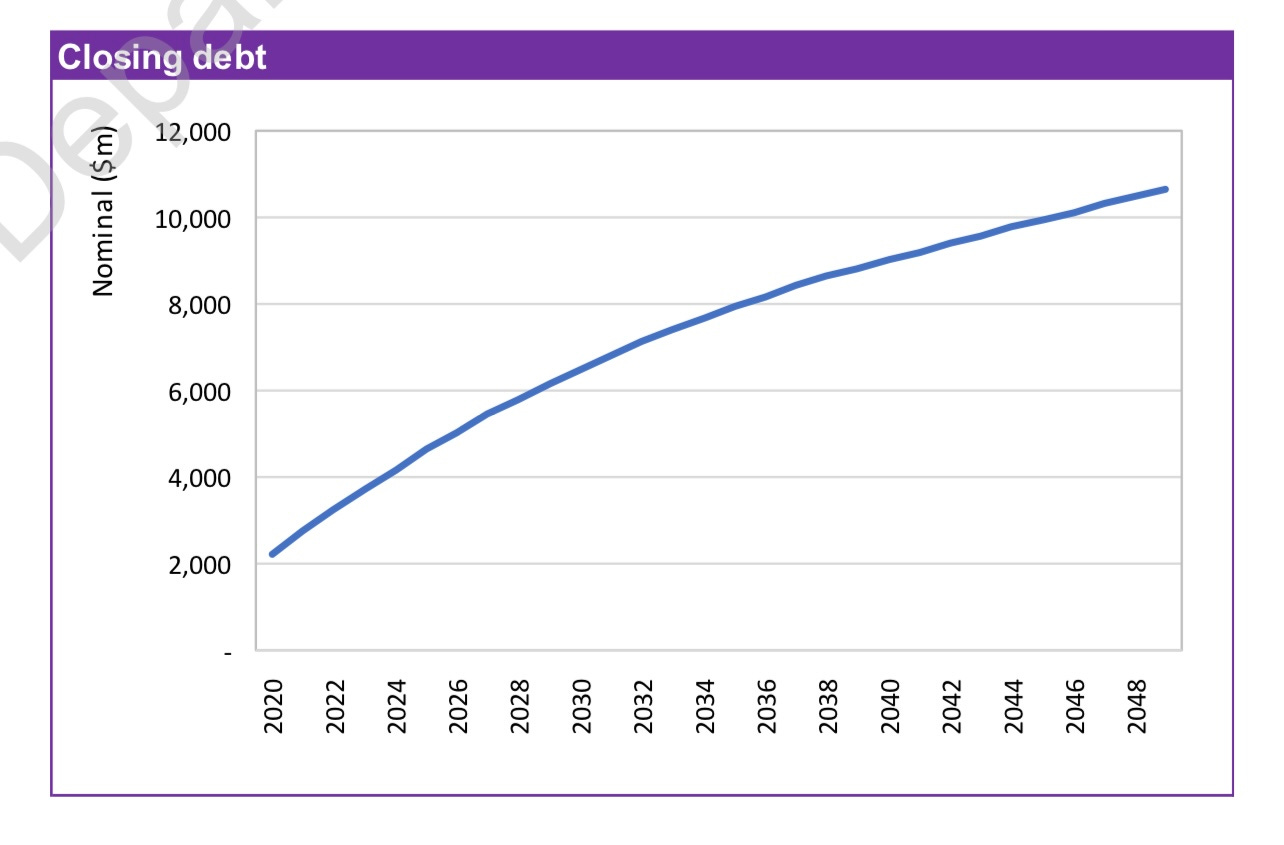

The chart below, taken from page 56 of the Information Memorandum, shows the debt increasing in the manner described above – starting at around $2 billion and increasing to over $10 billion in 2048.

The model assumes inflation at 2% and an interest rate of 3%. Other costs have not yet been determined by the government. When asked what work has been undertaken to estimate the costs that the water service entities will incur in relation to their engagement with mana whenua (including funding the production of Te Mana o te Wai statements to the relevant water services entities by as many as 1200 iwi and hapu) the government responded:

Explicit cost-related work by the Department is still ongoing and has not yet estimated the specific costs to the new water services entities in regard to supporting mana whenua participation. At this stage in the Three Waters Reform Programme, estimation of the overall ongoing operational costs for the entities once they are established are being projected by using the costs currently incurred by councils. These operational costs will include support for mechanisms that relate to mana whenua inclusion in three waters delivery services and functions.

Even more concerning is the RNZ article over the weekend in which Standard & Poor’s publicly expressed frustration about the lack of information relating to how the Three Waters reforms would be implemented. Specifically S&P expressed concerns about how the water assets would be transferred to the new entities – which undoubtedly would be a hellishly complicated and time-consuming process requiring careful planning and execution.

In addition S&P raised questions about the financial aspects of the reforms, such as whether the councils would receive any payments in return for the transfer of their assets and how large any payments would be, or how much debt councils would be left to carry, noting that “some councils would be left holding a high level of debt without a revenue line to cover that expense”.

Remarkably S&P’s uncertainty over potential credit rating adjustments relates not only to local government bodies but also to the New Zealand Government itself. Standard & Poor’s director of sovereign and public finance ratings Anthony Walker stated:

The agency could change its outlook as new information emerged, but we’re unlikely to actually upgrade or downgrade before we actually see that election outcome because that will be vital … [adding] the opposition had said it would scrap three waters if it won.

Not only does this intervention by S&P threaten to upset investor confidence in New Zealand’s credit strength at a time of volatility in the global financial markets but it also seems to indicate that Standard & Poor’s has serious concerns about the government’s ability to implement these reforms, and indeed if this government or Three Waters will survive the next election.

If the reforms do actually survive, we are told that the opening debt of the water services entities will be based on the existing local authorities debt allocated to water assets. When questioned by Act’s Simon Court, Minister Mahuta confirmed this as follows:

Water Services Entities will likely raise debt to finance payments to councils to settle three waters related debt, as well as ‘better off’ and ‘no-worse off’ payments. The ‘better off’ and ‘no-worse off’ payments are expected to require up to $1.5 billion of debt raising for water service entities ($1.0 billion better off; $500 million no-worse off).

This was a point highlighted by National’s Simon Watts in his speech to the House when the Water Services Entities Bill was introduced to Parliament in June:

On day one, before a single measure of pipe is laid, these entities will be in debt because Labour couldn’t sell these reforms: $1.5 billion of borrowing, offering councils to try and buy into these reforms. That money can be spent on pretty much anything. So on day one, the balance sheet of these entities will already be in debt and having to pay commercial interest rates. That could be nearly $100 million a year in interest payments alone. That shouldn’t surprise anyone because this Government is addicted to debt, and they are kneecapping these reforms before they even start.

As the charts above illustrate, the ‘free money’ currently being handed out to councils will remain outstanding as debt for decades. Whatever those councils choose to spend that money on – whether it is a new library or some improvements to a local park – will become debt that will require servicing by ratepayers long into the future. On top of this initial debt will be additional borrowings incurred year-on-year by the water services entities to finance the infrastructure upgrade.

The lenders to this project will be a large group of mostly international banks, sovereign wealth funds, pension funds and infrastructure investors – drawn primarily from the US, Europe and the Asia Pacific region. Some will be household names and could include institutions such as BlackRock, Goldman Sachs and HSBC. Others very deliberately keep a low profile and only appear when things start to go bad. When nine toll roads built by the Spanish government around Madrid went bankrupt a few years ago a group of hedge funds who were lenders to the project threatened to pursue the Spanish government in the courts for a “zillion years” until they received a full payout of the €4.5bn debt owed to them.

China has also been an active provider of finance for infrastructure projects in the Pacific in recent years which has seen it attract criticism for engaging in so-called “debt-trap diplomacy” – an accusation which it rejects. However even Nanaia Mahuta, in her role as Foreign Minister, has voiced her concerns stating that “there is a real challenge around the level of loans that have been put into specific countries”. Given its involvement in global infrastructure investment it seems highly possible that Chinese financial institutions will also participate in the proposed financing of Three Waters.

A Deloitte report to the Department of Internal Affairs described the potential lenders in the following manner:

The structural changes proposed, combined with the scale of the anticipated investment into the sector over a long timeframe, will create an appetite for investment from the financial services sector. We would expect that private equity, sovereign wealth funds and other international investors would welcome the additional ability to invest in New Zealand infrastructure and are aware of parties who are already at an early stage of investigating that opportunity.

However, importantly there is one more party that will very likely form part of the group of lenders which will make the whole structure immeasurably more complicated and create tensions that could rip the country apart. Minister Mahuta plans to allow iwi to also participate in the Three Waters financing as lenders. Thus the massive debt owed by the water services entities, and the interest payments that will be required to service that debt, will in part be paid to iwi that are also lenders.

Minister Mahuta described this in her June 2021 Cabinet Paper:

I note that some iwi/Māori have raised the question of whether there is an opportunity to invest in water services entities. As a general proposition, the entities will have flexibility in relation to how and where they source debt finance.

Iwi/Māori are a potential source of finance. It is recognised that iwi/Māori bring a different perspective, including considerations of intergenerational benefits and outcomes that may be aligned to wider reform objectives. Separate to issues of ownership, there is no reason why iwi/Māori should not be a source of debt finance to the proposed entities or in relation to specific projects that the entities will deliver. Ultimately, this will be a decision for each entity’s board.

Last week I asked the government for confirmation that they still intend to allow iwi to provide debt financing to Three Waters. The Department of Internal Affairs did not respond before this article was published.

Given the immense influence that iwi already have in the Three Waters structure at the Regional Representative Group level via co-governance and at the operating level via the Te Mana o te Wai statements, it makes sense for institutional investors to welcome some iwi into their lender group. It will give the lenders huge negotiating power if (and when) the terms of the financing need to re-negotiated with the water services entities, and in particular, if the structure’s financing becomes stressed.

Iwi who are also lenders will therefore have governance rights within the Three Waters structure as well as creditor rights. When exercising any of those rights they will be entitled, as a matter of law, to take into consideration all of their commercial interests which means that they may, for instance, choose to exercise governance rights in a manner that benefits the lenders or visa versa. These cross-interests can greatly complicate, and in some instances, frustrate the restructuring of a business’s finances. Following lessons learnt from the 2008 Global Financial Crisis most international financing documentation now prohibits or at a minimum severely restricts this type of behaviour.

There has been much discussion about the privatisation risk for Three Waters but there is, in my opinion, a far greater risk that the country’s control of its water assets will be diluted in a financial restructuring as lenders (and iwi) demand greater representation at the governance levels of the structure at the expense of other stakeholders. In this context control matters more than legal ownership. Lenders will in all likelihood have security over the revenue stream (i.e. the water rates) but not over the pipes and infrastructure. The government’s Information Memorandum describes this in the following manner:

Revenue security appears the most likely option given the sensitivity of water assets and issues with enforcement, with the WSE providing a security interest over water revenues.

This is exactly what lenders, and in particular hedge funds that invest in financially distressed assets, want – control of a country’s entire water revenues. Financial restructurings of businesses of this size and scale usually take place in stages. At first the problems are too numerous and difficult to face all at once. Thus a government can be willing to commit more taxpayer money in order to save face and delay the problem for another day. But this is usually only a temporary fix before the inevitable restructuring occurs when it becomes politically impossible to commit more public money to a troubled project.

A full restructuring of the finances of Three Waters would likely be drawn out over years and be a brutal attritional negotiation that will pit the government, iwi, local councils and lenders against each other in a contest for control of the country’s water revenues. It would clearly be highly political and divisive for the country. The rewards are so great in these situations that the lenders will not rush – after all, ratepayers who are being squeezed in the meantime have nowhere to go. Given that iwi will be wearing multiple hats – having significant influence at the operating and strategic levels of the structure as well as potentially being lenders, it would be logical for the commercial lenders to work together with iwi lenders to achieve an outcome whereby lenders and iwi have greater representation at the strategic level of Three Waters at the expense of other stakeholders.

The upgrade of the country’s infrastructure is undoubtedly required but, despite the government’s protestations, there are in fact lower risk financing options available. Immediately following last week’s local government election results (which were widely viewed as a referendum on Three Waters), the Prime Minister again defended her proposals by stating:

That is the reason we are pursuing this – the alternative to Three Waters is rate rises in the thousands because of the additional water infrastructure that is required, no one’s out campaigning on that.

This is simply not correct. Analysis conducted by Castalia on behalf of Communities 4 Local Democracy shows that all capital expenditure requirements for the next 20 years can be financed without increasing water bills or changing council debt caps. The Castalia report states:

Castalia finds that the government’s modelled $97 billion capital expenditure under the mega entity reforms is financeable for 20 years under the C4LD reform model without increasing water bills or changing council debt caps. Castalia’s modelling matches exactly the WICS mega entity capex programme in terms of timing and amount spent. Of course, a range of financing options are available that would make financing even more accessible.

The proposed Three Waters financing by itself is extremely aggressive and risks following the same ill-fated path as other highly leveraged utilities elsewhere in the world such as Thames Water. However when combined with an overly complicated and unbalanced governance structure it could prove to be ruinous to the country’s finances and deleterious to its social fabric. The local government elections have sent a message. Tinkering with these reforms will not suffice. Three Waters needs to be flushed.